|

LI DENGHUI came to my attention in an

obscure item as a prized pupil for Standard I in 1887,

albeit under the name “Lee Teng Hwee”.

Subsequent research into the recently

acquired ACS Journal for 1889 confirmed that he won prizes

for Dictation and Grammar in1889 when he was in Standard

IV. No bookworm, he joined the Cricket Club and was

elected Secretary and Treasurer, and contributed to the

Journal with a short reflection on the proverb, “Where

there’s a will there is a way.” What manner of student was

this, and what was the story?

Born in 1872 to the family of a poor

farmer with a small trading business in a small West Java

town near Batavia (Djakarta), he was the eldest in a

family with five brothers and two sisters. He studied at

an elementary school, going by horsecart, but staying at

home on rainy days to help his mother look after his

siblings. His mother’s death in 1885 when he was just 13

affected the business but Denghui showed little interest

in the business or domestic chores. After his father

remarried, he agreed to let the restless lad go to

Singapore to further his studies in 1886 when he was 14

years old.

He arrived fairly soon after ACS was

founded, and was entrusted to his father’s business

associate, one Mr Tan, who looked after him and arranged

for him to be enrolled in the school. With an emphasis on

English, science and mathematics, together with regular

Bible study, a number of students became Christians, and

Denghui’s Christian faith and his belief in the value of

loyalty, purity, generosity and love came from his three

years at ACS.

In his second and third year, he had

all his meals with the Rev William Oldham, while he would

wander off after church on Sundays to ponder over the

window of knowledge which he widened when he went overseas

to study Greek, Latin, French, the arts and literature of

the Renaissance, and English Literature – a background

from which he was later to teach at Fudan University.

At ACS, he was a good scholar, and must

have impressed Oldham who accompanied him to Batavia some

time in 1889 (before going on medical leave in America).

With Oldham’s encouragement and financial assistance from

the Methodist Mission, he sailed for America in 1891 where

he spent some time at Ohio Wesleyan University preparatory

to admission to Yale from where he graduated with a BA

degree in 1899.

His Christian background now encouraged

him to answer Bishop Thoburn’s call for volunteer

missionaries to teach in India and Malaysia, as did James

Hoover – who later became a key Methodist missionary in

Sarawak. Both men actually sailed together to Penang where

they joined the staff of ACS Penang, and were members of

the school committee along with Dr. B. F. West, G. F.

Pykett and J. W. W. Hogan in 1900.

The idealist

in action

An article by Zhuang Qin Yong in the Journal of Humanities

& Social Sciences, Vol III, 1982/83 shows Li Denghui as an

intensely patriotic Nanyang Chinese, bitterly disappointed

at the failure of the efforts by early Chinese patriots

like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao to modernise China. He

thus resolved to devote his life to serve its people. He

founded a debating society in 1899, similar to that

established earlier in Singapore by Dr Lim Boon Keng whom

he met in Penang. He linked the causes of the problems

besetting China to a blindly conservative mentality, an

incompetent, corrupt and unjust ruling class, the

exclusion of women from education, and the observance of

ancestral worship. This led him towards the need for

reform in China.

Deciding that his future lay in social

action, Li Denghui left Penang, and spent three years in

Batavia unsuccessfully pursuing his ideal of providing a

new kind of education. In 1904, he revisited Penang,

meeting a number of other Nanyang Chinese with similar

ideals – Dr Wu Lian Teh, Dr Gu Li Ting and Hong Mu Huo –

firming up some ideas which were later applied in China,

where he spent the rest of his life.

He arrived in Shanghai in October 1904, organised the

World Chinese Student Federation in July 1905 and was its

first President, aiming to promote social justice in

China, unite Chinese students studying overseas, and help

members secure employment, medical care and legal advice.

Similar associations were set up in Penang, Qingdao,

Fuzhou, Hawaii and Singapore. Most of the original members

of the federation were Christians and patriots.

At almost the same time, he was

appointed supervisor of Fudan Public School by its

founder, Ma Xiangbo, a Christian, whose intention was to

select high school students by examination and train them

in higher level subjects in the English language thereby

enabling them to gain admission to European universities

for specialised subjects.

In 1913, when Ma Xiangbo had to leave

China, Li assumed the position of Principal, teaching

several subjects such as English, Logic and Philosophy. In

1917, when Fudan Public School became a university with a

modern curriculum in the humanities, natural sciences and

business as well as modern European languages, he became

its first President. Unique in being a private

institution, it was staffed mainly with teachers who had

been trained in the West.

As President of Fudan University, he

lent active support to the May 4 Movement that had started

in Beijing and spread to Shanghai in May 1919, providing

refuge for students who had been dismissed from Beijing

University for their involvement.

Despite the efforts of Li to defend the

actions of the students as patriotic, the authorities took

a hard line, arresting and punishing them. This resulted

in a general strike by students in Shanghai, supported by

public works personnel. In the ensuing confrontation, the

Republic of China Student Union convened a meeting to

elect representatives, attended by Li. When things had

quietened down, Li chaired a public talk attended by more

than 100 Chinese students who had studied in Europe and

America, and encouraged them to work hard and diligently

in order to reform the new China.

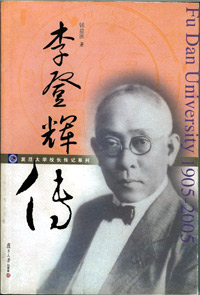

Celebrating

the Fudan Centenary – 1905 – 2005 Celebrating

the Fudan Centenary – 1905 – 2005

An unexpected source of Li’s role in the social and

educational development of China in the period before the

war has come from a recent publication of his biography by

Fudan University celebrating its centenary this year.

In reviewing his more than 30 years of

educational leadership in a society that was in a sorry

state, he noted (in a radio broadcast in May 1940) that

the education provided by Fudan had progressed

significantly from a mere high school to a full-fledged

university, and from a basic academic curriculum to

specialised scientific studies and, with the development

of physical culture, students had become more robust.

Unfortunately, this was insufficient;

real social progress is the result of moral integrity by

which teachers have to lead by example. He himself

realised this when he recognised that his right to demand

strict moral standards of students could only be justified

and authenticated by his personal commitment to these same

standards.

Such was the influence of his personal

and Christian values he absorbed when he was a student of

the Rev Oldham and later influenced by the Moral

Re-Armament Movement that promoted the "four absolutes" –

absolute honesty, absolute unselfishness, absolute love

and absolute purity. |